The importance of bracing

What is bracing?

Simply, “bracing” is recruiting the muscles of the torso so as to stabilise the spine (whichever position it is in) while other parts of the body are moving and generating force.

Sounds like it just means core strength

We tend not to use the phrase “core strength” since it is quite a vague and poorly understood term. We prefer “torso stability”, which we think is clearer and more accurate. Bracing is a technique for generating and training torso stability.

Why should we brace?

Bracing serves two main purposes:

Ensuring that the spinal cord and intervertebral discs are protected when forces are applied to the torso

Ensuring efficient transfer of force from the muscles generating the force and the contact point(s) at which that force is applied (e.g. a dumbbell or barbell, the pedal of a bike, a foot or hand hold on a rock climb)

In gym-based resistance training we are deliberately (and slightly artificially, relative to our actual sports) applying external load to our limbs that we must then resist and/or overcome so as to stress our body such that it adapts, not only metabolically, but also in terms of neuromuscular coordination and recruitment. Consequently, when we lift weights in the gym, bracing and practising bracing helps us to (a) learn to coordinate the application of force by our limbs with the dynamic stabilisation of the spine, (b) maximise the external load that we can apply to our limbs (i.e. move more weight and get greater training stimulus), and (c) reduce injury risk while we do so.

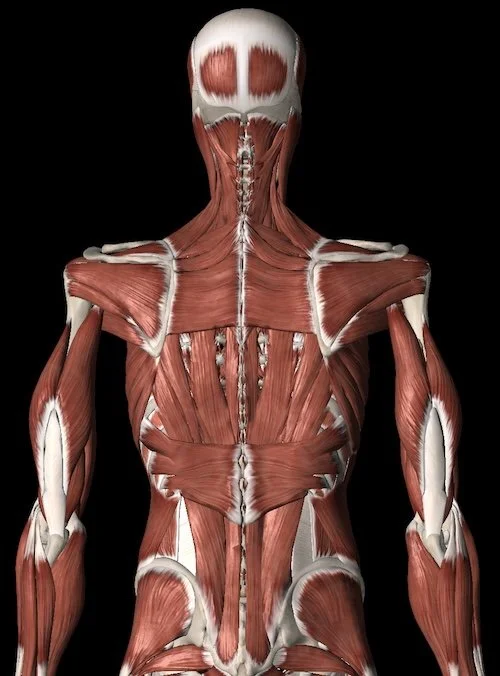

There are a great number of muscles that stabilise the spine and torso, many of them being relatively small, and although we can improve their strength and size, a more important goal of training them via resistance training is to coordinate their activation while the muscles of our limbs are generating force. Training the torso stabilisers in this way means that we are able to recruit them when needed during our much more dynamic sporting activities. This is what people mean when referring to “a strong core” – musculature in the torso efficiently stabilising the spine during movement for effective transfer of force and protection of the spinal cord. This doesn’t mean that training the stabilising muscles of the torso doesn’t improve their strength or fatigue-resistance, but it is not all that this type of training does.

When should we brace?

In gym-based resistance training we pretty much want to brace whenever we apply a load or weight to our arms or legs, i.e. during most exercises! This is slightly different to the case when peforming our sports, which is much more nuanced. When performing sporting activities, be it climbing, running, riding, skiing etc, we don’t want to be thinking “brace my torso and tense my core” (a) because there are more pertinent things to pay attention to, and (b) because doing so actually stiffens us up and makes our movement less efficient. Rather, we use gym-based resistance training, with deliberate emphasis on bracing and learning to brace in dynamically challenging exercises, so that during our sporting activities we are able to automatically recruit the stabilising muscles of the torso when we need our limbs to generate and transfer forces.

How should we brace?

Contrary to popular belief, when we “brace” or “engage our core” we should NOT suck in our belly. Rather, we should do the opposite!

When you brace, try to tense all around your abdomen imagining you’re about to be punched hard from any direction – you should be able to prod all around your belly, sides and lower back and feel the muscle tension. When you do torso stability or “core” exercises, use the exercises as an opportunity to practise this cue – e.g. don’t just do a plank, do it while continually sense-checking whether you are recruiting all of the stabilising muscles of the torso.

When doing other resistance exercises in the gym, e.g. during a squat, we always want to brace – always think, “Am I bracing, does my stance look ready and athletic?”

To brace while doing any resistance exercise:

Lengthen your spine as though a thread is pulling the crown of your head directly upwards

Puff your chest up without bending your mid/lower back and simultaneously pull/rotate your ribs down towards your belly button

Lightly pull your shoulder blades down towards your back pockets

Finally, without holding your breath, push your abdominals OUT in all directions, as though anticipating a punch from any direction (you should be able to prod all around your belly, sides and lower back and feel the muscle tension)

Breathing and bracing

When first learning to brace many people find that they either can’t breathe when tensing, or that they can only tense by holding a deep breath. Neither of these situations is correct or ideal!

If you struggle to breathe while bracing, start by just taking small sips of air, and over days and weeks, practise taking deeper breaths while not losing muscle tension. It helps to put your hands on your belly, sides and lower back to check whether you are losing tension while breathing.

When doing bigger compound exercises such as squats and deadlifts, it can be beneficial to deliberately take a large breath, into the belly, that we then force downwards and outwards into the belly and hold for the duration of the rep. This is known as the valsalva manoeuvre, and it is used in resistance training to add additional recruitment and rigidity to bracing, helping the spine resist the bigger forces that heavy squats or deadlifts demand of it.

Learning to brace

The best way to learn bracing is to practise with some simple exercises and then, over time, introduce more complex exercises that make heavier and/or more dynamic demands on your stability. We always start learning with the “McGill Big Three” exercises, that have been developed and popularised by Stuart McGill and Aaron Horschig:

The Curl-up

The Modified Side Plank

Modified Bird-Dog

For each of these exercises do 1–3 sets of 5 x 10 second holds (each side if applicable) with 5–10 seconds rest between holds. The first few reps might feel easy… the last few probably won’t! Doing this every day or two for four weeks will have a significant effect on your torso stability.

Lie on your back with one leg bent

Lift your head UP off the floor (not forward), just 2 or 3 centimetres

Raise your elbows off the floor

Brace and breath, as described above

Hold for 10s, relax for 5–10s and repeat for the prescribed number of reps

Lie on your side, with your elbow and hip on the floor, with flexed hips and knees.

Brace and breathe, as described above

To come up off the floor, drive your hips forward and up, as though you were doing a squat, so that your contact points with the floor are your elbows and your knees

Get and keep your hips as high as you can, with your trunk/torso perpendicular to the floor – no collapsing forwards or falling backwards

Keep bracing your trunk and abdominal muscles HARD. Squeeze your glutes at the top

Hold for 10 seconds, come back down with total control, remaining braced on the descent, relax for 5–10 seconds and repeat for the prescribed number of reps

In this exercise your spine and pelvis should remain in a neutral position at all times.

Before you move your leg and/or arm, brace as described above and try to eliminate any movement from your pelvis and spine. Your pelvis and both shoulders should remain parallel to the floor at all times. Take a video or get someone to watch you if you’re not sure whether you’re moving correctly.

Get into an all-fours position, hands under shoulders, knees under hips, toes tucked.

Brace and breath, as described above

Then with out any pelvic or spinal twisting or rotation, slowly push one leg back (as though pushing into the pedal of a bike) and raise the opposite arm, thumb pointing up, fist clenched. Don’t push your foot high above the floor – you will lose control of your spinal position.

Hold for 10 seconds and, remaining braced, come back to the starting position with total control, relax for 5–10 seconds and repeat for the prescribed number of reps.

Once you have mastered these basic exercises, not only will you feel more stable in your torso during resistance training, your sport(s) and your daily life, but you will be ready to start progressing the complexity of your stability training into more challenging and sport-specific movements.